Bridging the Divide

Neuroscience and the Learning

May 30, 2025

One of the biggest controversies in education centers on learning styles. Those who say that learning style differences exist believe, for example, that some people learn better by hearing while others learn better by seeing. But most prominent psychologists cite research revealing that “auditory” and “visual” learners learn similarly and conclude that learning styles don’t actually exist. This debate matters because how we understand learning has concrete implications for educational policy and teaching practices. All this means that it’s worthwhile to bring fresh perspectives from neuroscience to this long-simmering and

The following is an excerpt from the article originally published in ElementsEd Issue 02. The article is written by Barbara Oakley.

One of the biggest controversies in education centers on learning styles. Those who say that learning style differences exist believe, for example, that some people learn better by hearing while others learn better by seeing. But most prominent psychologists cite research revealing that “auditory” and “visual” learners learn similarly and conclude that learning styles don’t actually exist. This debate matters because how we understand learning has concrete implications for educational policy and teaching practices. All this means that it’s worthwhile to bring fresh perspectives from neuroscience to this long-simmering and

When Definitions Collide: Style Versus Ability

One keen opponent of theidea of learning styles is Daniel Willingham—a psychologist who has done admirable work in education.

Ability is that you can do something. Style is how you do it. Thus, one would always be happy to have more ability, but different styles should be equally desirable. I find a sports analogy useful here. Two basketball players may be of equal ability, but have different styles on the court, one being a risk-taker, and the other quite conservative in his play. (Sometimes people say it’s obvious that there are learning styles because blind and deaf people learn differently. This is a difference in ability,

not style.)

It seems like a clear difference. But what if ability affects style? Let’s draw again on sports, as Willingham did, to show you what

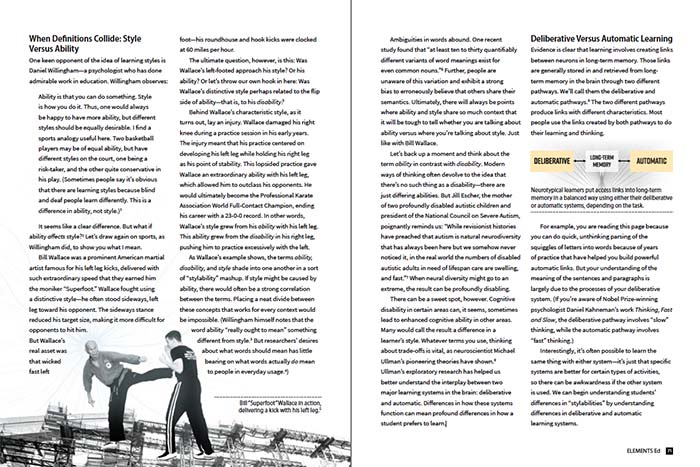

Bill Wallace was a prominent American martial artist famous for his left leg kicks, delivered with such extraordinary speed that they earned him the moniker “Superfoot.” Wallace fought using a distinctive style—he often stood sideways, left leg toward his opponent. The sideways stance reduced his target size, making it more difficult for opponents to hit him. But Wallace’s real asset was that wicked fast left foot—his roundhouse and hook kicks were clocked at 60 miles

The ultimate question, however, is this: Was Wallace’s left-footed approach his style? Or his ability? Or let’s throw our own hook in here: Was Wallace’s distinctive style perhaps related to the flip side of ability—that is, to his disability? Behind Wallace’s characteristic style, as it turns out, lay an injury. Wallace damaged his right knee during a practice session in his early years. The injury meant that his practice centered on developing his left leg while holding his right leg as his point of stability. This lopsided practice gave Wallace an extraordinary ability with his left leg, which allowed him to outclass his opponents. He would ultimately become the Professional Karate Association World Full-Contact Champion, ending his career with a 23-0-0 record. In other words, Wallace’s style grew from his ability with his left leg. This ability grew from the disability in his right leg, pushing him to practice excessively with the left. As Wallace’s example shows, the terms ability, disability, and style shade into one another in a sort of “stylability” mashup. If style might be caused by ability, there would often be a strong correlation between the terms. Placing a neat divide between these concepts that works for every context would be impossible. (Willingham himself notes that the word ability “really ought to mean” something different from style. But researchers’ desires about what words should mean has little bearing on what words actually do mean to people in

Ambiguities in words abound. One recent study found that “at least ten to thirty quantifiably different variants of word meanings exist for even common nouns.” Further, people are unaware of this variation and exhibit a strong bias to erroneously believe that others share their semantics. Ultimately, there will always be points where ability and style share so much context that it will be tough to tell whether you are talking about ability versus where you’re talking about style. Just like with

Let’s back up a moment and think about the term ability in contrast with disability. Modern ways of thinking often devolve to the idea that there’s no such thing as a disability—there are just differing abilities. But Jill Escher, the mother of two profoundly disabled autistic children and president of the National Council on Severe Autism, poignantly reminds us: “While revisionist histories have preached that autism is natural neurodiversity that has always been here but we somehow never noticed it, in the real world the numbers of disabled autistic adults in need of lifespan care are swelling, and fast.” When neural diversity might go to an extreme, the result can be

There can be a sweet spot, however. Cognitive disability in certain areas can, it seems, sometimes lead to enhanced cognitive ability in other areas. Many would call the result a difference in a learner’s style. Whatever terms you use, thinking about trade-offs is vital, as neuroscientist Michael Ullman’s pioneering theories have shown.8 Ullman’s exploratory research has helped us better understand the interplay between two major learning systems in the brain: deliberative and automatic. Differences in how these systems function can mean profound differences in how a student prefers